And so, it’s happened. It happened to The Huffington Post. It happened to The Guardian. And now it’s happened to us, too. Oh, how the mighty (!) have fallen.

It was always going to happen, really, the creeping inevitability of bitesized news reporting finding its way into the SLAIW camp. The more articles I read entitled “The 47 things only white girls born between 1988 and 1992 will remember[1]” or “The 17 ways you can spruce up your autumnal brunch”, the more the listicle format worms its way into my brain, until I open my wardrobe in the morning and announce to nobody in particular I’m about to compile the “8 accessories that will cover up the gravy stain on your favourite top so you can get away with wearing it again before it gets washed”.

Buzzfeed has a lot to answer for. Mainly, where the last eight months of my productivity went, but also how it managed to take over the whole internet without us even really noticing. Its rise has been stratospheric, its influence far-reaching, and its combination of charm, interactivity, readability and cat gifs irresistible.

So irresistible, in fact, that – without further hesitation – I present The 5 things you do in English[2] that you might not know have actual, technical names (snappy, right?).

1. Tmesis

The English language has prefixing (re-establish) and suffixing (establish-ment), and these prefixes and suffixes can be stacked to (sometimes) ridiculous extents (anti–dis-establish-ment–arian–ism). However, unlike some languages of the world (including Portuguese, Arabic, and Tagalog, to name just a few), English doesn’t have infixing, the addition of a particle in the middle of a word to change its meaning.

Except, we kind of do. In language originating from (or often used to parody) hip-hop culture, words are modified from house and shit to hizouse and shiznit, for example.

More commonly, English has a creative process called tmesis – the insertion of a full word into another one, not for the communication of semantic information, but for emphasis or effect. Swear words are most commonly used, creating strings like fan-bloody-tastic, cata-fucking-strophic and seventy-shitting-seven. (And it doesn’t just have to be one word either. Barney Stinson’s catchphrase “Legen-wait for it-dary” is an example of tmesis.)

The process is creative, but you can’t just throw in a word willy-nilly; the phonotactic structure of the word is important. The infix comes before the main stressed syllable of the word (so you wouldn’t get fantas-fucking-tic), or in a logical morpheme break (so you wouldn’t say seven-shitting-ty-seven). So, true to form, when The Thick of It‘s Malcolm Tucker peppers his language with fantastically creative swear words, he goes for “Enough. E-fucking-nough” (S3E2) and “I am totally beyond the realms of your fucking tousle-haired, fucking dim-witted compre-fucking-hension!” (S4E7). It’s a process not native to English that nevertheless has developed its own structure – pretty cool, right?

2. Mondegreen

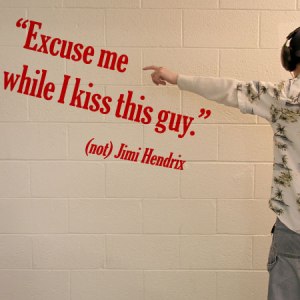

Ever misheard the lyrics to a song, singing something that sounds similar but you later realise (usually to public embarrassment) is quite wrong? That’s called a Mondegreen!

The term was coined by Sylvia Wright in 1954, in reference to a 17th Century ballad called The Bonnie Earl o’ Moray. The final lines of the poem are:

“They hae slain the Earl o’ Moray // and laid him on the green”

while Wright (mis)heard

“They hae slain the Earl o’ Moray // and Lady Mondegreen”.

The misheard line is homophonic, but quite different in meaning.

Other classics include:

Glady the cross I’d bear — Glady the cross-eyed bear

Round yon virgin mother and child — Round John Virgin, mother and child

I am the Lord of the dance, said he — I am the Lord of the dance settee (<3)

Hold me closer tiny dancer — Hold me closer, Tony Danza

This whole scene from 27 Dresses, including “electric boobs” for “electric boots”

Britney Spears’ ‘If You Seek Amy‘ uses a kind of reverse Mondegreen, where mishearing the lyrics offers (what one would imagine is) the proper, NSFW meaning.

A particular favourite from my brief emo youth was a song by The Used called Light With a Sharpened Edge, which contains the deep, meaningful lyrics “It’s not me, buried wreckage my soul”, which my brain translated to “It’s not me, Ready Brek is my soul”. Thinking about it, that is both an example of a Mondegreen, and a kind of…

3. Spoonerism[3]

You may well be more familiar with this one. Spoonerisms occur when you switch the first ‘segment’ of a word with the first ‘segment’ of the following word. I say ‘segment’ in this way because it could be the first letter (belly jeans for jelly beans), the first morpheme/syllable (cubic toilicle for toilet cubicle[4]) or something less formal than that (my friend’s mum once yelled “close the door, I’m trying to keep my womb draw” instead of “room warm”, which is Spoonerlike).

Spoonerisms are often relied upon for tongue twisters, like “I’m not a pheasant plucker I’m the pheasant plucker’s son, I’m only plucking pheasants ’cause the pheasant plucker’s done”[5] (say it speedily, you’ll get it). They’re also used as the base for many jokes, including my favourite:

What’s the difference between a lobster in a bra and a dirty bus stop?

One’s a crusty bus station and one’s a busty crustacean.

Anyone? No??? Whatever.

4. Metathesis

Spoonerisms actually fall under the larger umbrella of metathesis, the switching around of letters, parts of words or whole words. It is a linguistic feature of loads of languages, occurring as a general rule to convey a different meaning, or to avoid a clash of sounds prevented by the language’s makeup.

In English, it’s once again not a general rule, but is a really common feature of everyday speech, particularly in children. My younger brother used to say aminal and demin instead of animal and denim, and I can’t count the times I’ve heard people call sudoku suduko through the same simple process.

You might think it’s just a slip of the tongue, but in actual fact, loads of English words have been created/changed through metathesis. The English words wasp, bird and horse were, in their original Old English forms, wæps, bryd and hros, and it’s through a simple occurrence of metathesis (and this switching of the sounds catching on, and propagating through the country) that we have the words as they are today.

5. Contrastive focus reduplication

In this video, the tendency for English speakers to repeat the same word in order to convey a different meaning is highlighted as A Bit Daft. But it’s not! Again, reduplication (the repeating of a word, or part of a word) is a grammatical feature of many languages other than English (like, LOTS) , but it is used in English too. Consider:

“Is it hot today?” “It’s hot, but it’s not hot hot.”

“Do you want a drink, or a drink drink?”

“I’m grown, but I’m not grown grown.” (NSFW expansion)

These are all prime examples of contrastive focus reduplication! Somehow, the repetition of the same word twice (often with exaggerated/altered stress) manages to add extra nuance of meaning to the sentence. As this paper by Ghomesi, Jackendoff, Rosen & Russell explains, CFR can highlight a more prototypical example of the thing you’re talking about, like salad salad (as opposed to potato salad) or milk milk (as opposed to soy milk). For a lovely explanation of this, Gretchen McCulloch wrote a great piece for the Slate!

It can also highlight a more specific thing, like in the drink drink example above, suggesting an alcoholic drink rather than any kind of beverage.

“We should go out.” “We are out.” “No, I mean out out.”

This example in particular is interesting, as I’ve seen it used in two ways that are related, but quite different. Firstly, my friend said it to me a couple of weeks back to suggest that we get our gladrags on and go out in town one night. So, the reduplication specifies that, rather than just going ‘outside’, we should ‘go out’, in its conventionalised cultural sense of fancy clothes, drinks and dancing. I also saw it used on a bag, currently for sale in Dorothy Perkins!

I also heard it used on Orange Is The New Black[6], spoken by inmate Piper Chapman, who had been temporarily released from prison on furlough to attend her grandmother’s funeral (see below). Here, the same construction is used but this time to specify that her ‘outness’ is temporary.

So the same construction is used in both senses to be more specific, to restrict the same concept, but in the first instance it’s restricted culturally (for want of a better word), and in the second it’s restricted temporally. Aint English clever?!

(Eh, it’s clever, but it’s not clever clever.)

—

Thanks for reading – your favourite examples of any of the above are very much welcomed in the comments! I’m now going to find out which Friends character is most like my penis. No, really.