This is our first guest post (because Hannah and Kate are apparently useless at updating this much-loved blog and we need help), brought to you by linguistic clever-clogs and punster supreme, James Chetwood.

One of my favourite episodes of Brooklyn Nine-Nine is the one with the Jimmy Jab Games – a multi-event workplace procrastination competition, featuring challenges such as the Monster Mouth Bagel Toss.

The Jimmy Jabs were invented by Jake Peralta and are named after the President of Iran, Armen Jimmy Jab:

Or, as Rosa points out, Ahmadinejad:

But it doesn’t matter, because the most important thing is that they’re going to play the Jimmy Jabs, and they’re all psyched!

So Jake got the name wrong. But the fact the Jimmy Jabs are still called the Jimmy Jabs, even though the person they’re named after isn’t called Jimmy Jab, doesn’t matter, because names don’t really have any meaning, do they? Well, actually, I think they might – at least in some ways.

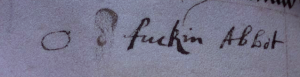

I’m doing a PhD in History, and for the last two-and-a-bit years I’ve been looking at names: finding, listing, counting and (in theory) analysing names. About 15,000 of them.[1] Linguists generally think that names have no meaning, or no ‘sense’, because they don’t explain anything about the people who bear them. But, the more I look at names, the more it seems to me that names do have meaning.

Unlike other nouns, names only refer to one person or thing, and nothing else. With normal nouns, I can talk about a particular dog, cat or boat, but I can also talk about the class of things that are dogs, cats and boats, because there’s something about all dogs, cats and boats that make them dog-like, cat-like and boat-like. I take part in this kind of exchange every day:

Other person: Fucking hell mate, control your fucking dog will you?

Me: Sorry mate. But that’s what dogs are like. He’s just trying to play. Chill out.

But this doesn’t work for names, because there’s nothing about a James, a Hannah or a Kate that makes them more or less like any other James, Hannah or Kate. Each James is unique, as is each Hannah and each Kate.

So names are just labels we use to refer to specific people and can’t be used in any general sense. At least that’s the theory. But then there’s When Harry Met Sally:

Harry: With whom?

Sally: What?

Harry: With whom did you have this great sex?

Sally: I’m not gonna tell you that!

Harry: Fine, don’t tell me

Sally:…Shel Gordon

Harry: Shel? Sheldon? No. No, you did not have great sex with Sheldon.

Sally: I did too!

Harry: No you didn’t. A Sheldon can do your income taxes. If you need a root canal, Sheldon’s your man. But humpin’ and pumpin’ is not Sheldon’s strong suit. It’s the name: ‘Do it to me Sheldon! You’re an animal, Sheldon! Ride me big…Sheldon’. It doesn’t work.

Like it or not, names have meaning (sorry Sheldon). In this case it’s associative meaning.[2] We know from prior experience what sort of person we expect a Sheldon to be. We associate people called Sheldon with certain attributes. Whether we’re right or wrong is another matter, but we do this all the time. And we’re often right, because names can tell us a lot about the people who bear them.

The accuracy with which someone’s name can determine their proficiency at humpin’ and pumpin’ is, admittedly, fairly low. But names are usually pretty good at telling us other things, including where someone is from, how old they are, who their family is and whether they’re a man or a woman.

This episode from Flight of the Conchords is funny (I think) because of the games it plays with Keitha’s name. It wouldn’t be funny if we didn’t know that Keith was a popular name in Australia, that people often name their children after their parents, or that female names in English often end in ‘A’.[3]

Because we know what type of people are called Keith, what type of people aren’t, and how names work in general, we’re able to make jokes about them. If names were completely meaningless, we wouldn’t be able to do this.

If Professor Richard Coates read what I’ve just written (he won’t, he’s basically the biggest name in, well, names, and has much better things to do), he’d probably say:

It’s amazing that arguments of this type persist, and they can only persist because we equivocate what counts as meaning. If these ‘mean’, they do not do so in a logically secure way. If I call my daughter Archibald, it’s hard luck on her, but I have committed no sin against logic or semantics, and it will be her name.[4]

Firstly, if ‘meaning’ something relies on doing so in a logically secure way, I’ve probably never said anything of any meaning in my life. Secondly, we actually do use words all the time that have meaning beyond pure semantic content. The way we say things – the specific words we use and the tone we say them in – all add nuance to, or even completely change the meaning of, what we are saying. The meaning of all language, at the end of the day, is about more more than semantic content.[5]

But I’d also question the idea that we have a free choice about what we name our children. This isn’t true – not really anyway. Our choices are dictated, or at least restricted, by the customs and fashions of the communities and societies we live in. This is one of the reasons names are actually really quite bad at doing what we assume they’re for: distinguishing people from one another. If that was what names were supposed to do, why would so many people have the same name?

Theoretically, we could use any random collection of speech sounds to create unique names. But we don’t. Usually we select them from a list of pre-existing names, most of which are used by thousands of other people. This list of names is an onomasticon (a mental dictionary of names), which is the name equivalent of a lexicon (a mental dictionary of words).

Like a lexicon, the names that appear in a person’s onomasticon depend on a number of things, including the language they speak and the experiences they’ve had in their lives. Every onomasticon is different, varying from place to place, community to community and generation to generation (as well as person to person). And, just like a lexicon, there might be hundreds, even thousands, of names that we’re aware of, but have never come across in our everyday lives, nor would ever consider giving to our own child.

The main determining factor of the names in someone’s onomasticon is where they’re from – the family, community and society in which they live. Each community has a set of names that are known and deemed acceptable by the other people within it. Depending on the place and period they live in, and the type and size of community, the number of acceptable names will vary, as will the degree to which people can deviate from the norm without being thought badly of.

Sometimes people want to make sure their child fits in, so may choose safe, traditional names. Some people want their child (and perhaps them by proxy) to stand out more than others – for example, the kind of people who would choose to call their child Saint.

Today, people often want to balance the need for their child to have a name that is both individual and traditional. They want a name that makes their child stand out and fit in at the same time. This is why we see so many ‘old fashioned’ names re-popularising. Perversely, in trying to strike this balance, people often alight on the same name for no apparent reason, causing previously unpopular names become popular. (Here’s looking at you, Amelia.)

And, while the ‘naming communities’ we are a part of today are larger, both in terms of the number of people and the number of names, than was the case a few hundred years ago, we are still occasionally flummoxed by unfamiliar names.

Jake doesn’t recognise the name Ahmadinejad because it’s not in his onomasticon – it’s not a name that’s present in his naming community. It isn’t that the sounds in the name, or even the spelling of it, are particularly difficult. It’s just that he doesn’t know it, so it’s difficult to recognise and remember. That’s why he transforms it in his mind into something that makes more sense to him.[6]

Richard Coates can call his daughter Archibald if he wants, and he might not be breaking any rules of logic or semantics by doing it. But the very act of doing so would be an overt flouting of the naming customs within his naming community. He may not care – but his daughter might not thank him when she’s older.[7]

So, even if it’s true that names don’t have logical semantic meaning, they do mean things to people, and they do contain meaning of some kind. Not all Richards will have exactly the same attributes. But there’s a pretty good chance that 20 people called Richard are going to have more in common with each other than they are with 20 people called Abdul or 20 people called Stéphanie. And, ultimately, whether he likes it or not, if you need a root canal, Sheldon’s your man.

James Chetwood is a PhD student in the Sheffield University History Department. His research is into naming patterns in medieval England. He spends too much of his time thinking about what makes a name a name, and why it’s OK to call a dog Molly but not Gary.