It’s Christmas!! I’m sitting here in my Fairisle knit jumper with reindeer and snowflakes on, I’m listening to Idina Menzel forcefully emote glorious Christmas music at me, and I still haven’t bought all my presents or finished putting the decorations up. The festive season is definitely upon us.

All of that is slightly beside the point for the purposes of this blog post, but damnit, I just really love Xmas.

Oh wait, sorry – not Xmas, Christmas.

This is a common complaint at this time of year and gets people really riled up. A quick poll of my small corner of Twitter (disclaimer: I did this last year and was so slow to write the post that I saved it for this year) shows that pretty much everyone prefers to write Christmas over Xmas. For some, it’s a matter of principle, that they don’t like shortening or abbreviating words, or because Christmas is more proper and more traditional. For others, it can be seen as ‘taking the Christ out of Christmas’, which is obviously something bad if you’re religious, but might be preferable for secular writers.

Of course, I’m not here to tell you whether you should be offended by something or not, but I think opinions about this are interesting considering the history of Xmas.

Xmas is no less full of Christ than Christmas in any way but spelling. Any quick Google will tell you this, but I’m going to put it here. With pictures. Lots of pictures. But the point stands; writing Xmas is not taking the Christ out of Christmas. And it’s certainly not any less traditional.

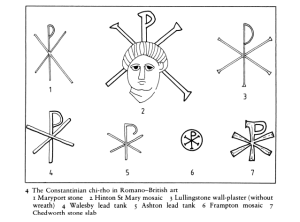

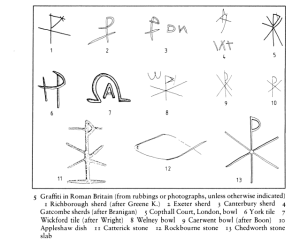

The ‘X’ in Xmas comes from the Greek spelling of Christ, ΧΡΙΣΤΟΣ. The first character, the X, is called Chi (pronounced ‘kai’, to rhyme with ‘high’). It had been used by pagan Greek scribes to mark notable or good things in the margins of texts, but in the 4th century it merged with the Rho to become a symbol.

The Emperor Constantine adopted it, went into battle under it and won, and it took off. All of a sudden this symbol had power across the Christian world. Indeed, the Christian cross as we know it didn’t start to appear in art produced in the British Isles until the sixth century. The Chi-Rho was the go-to symbol, and is still used today.

Charles Thomas, in his Christianity in Roman Britain to AD 500, has two excellent illustrations showing its development and use in different contexts:

[Google Books link, pp. 88-89]

And here, for your enjoyment, are some other cool things from early Christian history with XP on them:

Roman North Africa, 4th – 5th Century AD [ancientresource.com]

Roman North Africa, 4th – 5th Century AD [ancientresource.com]

The Hinton St Mary mosaic from Roman Britain in the 4th century, AD.

[more info from the British Museum]

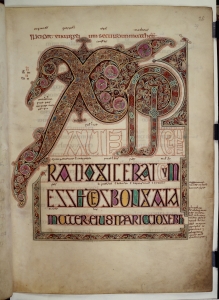

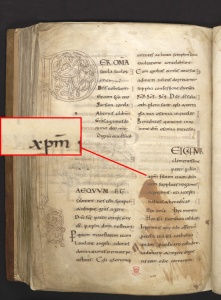

Most people were not literate in their own language, let alone in Latin or Greek and it’s very unlikely they recognised letters in the symbol. To most of the western Christian world, this symbol was Christ. The Chi-Rho was already in use in Roman Britain, and it comes into use again by the Anglo-Saxons from the fifth century. As I’ve written about elsewhere, scribes love abbreviating, and they really love symbolism, and XP combines those two in one heady mixture. XP is what we call a nomen sacrum, a sacred name, in which the symbol itself has power. In such cases, the abbreviation is not used to save space or effort, but because that form has more power than the full words. It was ‘not really devised to lighten the labours of the scribe, but rather to shroud in reverent obscurity the holiest words of the Christian religion’.*

It appears in the fanciest of manuscripts, taking up entire pages:

The Gospel of St Matthew in the Lindisfarne Gospels, the fanciest of manuscripts.

The Book of Kells. The fanciest of manuscripts.

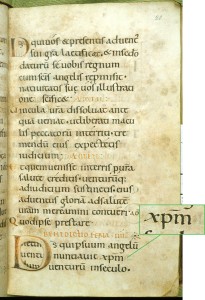

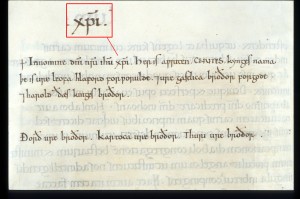

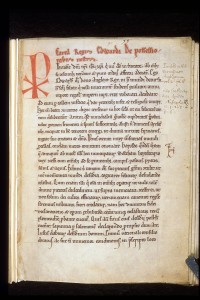

And in quiet little brown manuscripts, used as part of the normal text:

British Library, MS Additional 37517 f. 135v, a quiet little brown manuscript.

British Library, MS Harley 2892 f. 20

British Library, MS Royal 1 D IX f. 43v

British Library, MS Harley 391 f. 33

And oh wow in so many more places. See if you can spot it on each of these pages: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5.

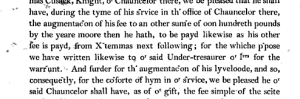

Of course, as we know, Christ is not just a stand-alone word, it also appears within other words (Christmas being the relevant example here). In 1485, for example, it’s used in christened:

1485 Rolls of Parliament. Any Kyng or Prynce in England Xp̄enned.

And in 1573, in Christopher:

1573 J. Baret Aluearie, The long mistaking of this woorde Xp̃s, standing for Chrs by abbreuation which for lacke of knowledge in the greeke they tooke for x, p, and s, and so like~wise Xp̃ofer.

And eventually, just the X is used as a short-hand for the whole thing, as more obscurity slips in. The OED cites the first use of X in Christmas in 1551 by which time I imagine it’s long lost its symbolic power, particularly as, as the previous example shows, even in the sixteenth century, people were confusing the Greek letters Chi and Rho for the Latin letters Ex and Pee:

The earliest instance of X in Christmas,

in Edmund Lodge’s Illustrations of British History.

And then we see it cropping up in early 1900s greetings cards entirely detatched from any symbolic, early Christian meaning:

From the Ephemera Society

And on Victorian Xmas cards – none of which I’m able to post here for reasonable copyright reasons but which you should look at because they’re lovely – in the 1860s and 1870s.

So, not only is X- old as balls, in the medieval period it was even more powerful than Christ-. Feel free to use it for space-saving, festive, jolly, and religious reasons. And Merry Xmas!

[Note: What does surprise me – and if anyone can answer this, I’d be interested – is how low Xmas is compared to Christmas on Google NGrams. Possibly because it only contains published books, where Xmas might be rarer?]