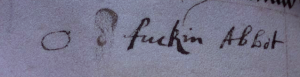

Last week I got to visit the manuscript that started it all. The one with the brilliant little note in the margin insulting some unpopular cleric with one of the earliest recorded instances of the word fuck:

Brasenose College MS 7, f.62v [photo mine, with thanks to Brasenose College, Oxford and Llewelyn Morgan]

What this picture shows is one full page of a fifteenth-century manuscript. The two main columns are a section of Cicero’s De Officiis – a moral treatise on good behaviour – which was the second-most frequently copied text of the Middle Ages. And at the bottom of these two columns someone has come along and written the following:

1. false are the works wich this Abbot writ in the abbie of Osney alias Godstow 1528

2. O d fuckin Abbot

This handwriting is found on several pages throughout the manuscript and, very unusually, it gives us a date – 1528 – so we know exactly when it was added.

Writing notes on manuscripts was common practice. Manuscripts weren’t viewed as they are now, and they weren’t equivalent to our modern books. We see a printed book as a complete object; to write on it is to defile it. Medieval manuscripts, despite being rarer than our mass-produced books and MUCH more expensive, were constantly added to, first by editors and correctors, then by later readers or students. In fact, this was a practice which continued for centuries, as described in this excellent post about Mr Bennet’s library.

On this manuscript there are actually two layers of annotations: the handwriting shown here, and the work of a second, much more prolific person, who wrote all over it, clearly engaging very closely with the main text.

But to get back to the fuckin Abbot.

The first line tells us something about the possible identity of the abbot: the Abbot of Osney in Oxford in 1528 was John Burton and, as it happens, he wasn’t a particularly popular abbot.

At that time fuck was a word used to describe sex. It wasn’t used as a swearword as we’d use it today. So the ‘fucking’ here is probably being used literally: ‘Oh, that abbot who fucks a lot’. (Someone has tried to find evidence of this but the worst they could find was one pregnant nun nearby who may, or may not, have been shagged by the Abbot. If he WAS trying for Casanova’s record, he kept it quiet).

‘BUT WHAT ABOUT THE D?’ I hear you cry.

The only mention of it that I’ve found suggests that it’s an abbreviation of damned or damn, as in, ‘O damned fuckin Abbot’.* This isn’t an unreasonable thought: as I discussed in an earlier post, medieval scribes loved abbreviating. They loved it more than they loved doodling in margins and sharpening their quills.

However, when they abbreviated they typically added a mark – a dash, or a squiggle – to show that something had been missed off. Not always, but enough that the absence of such a mark here is unusual.

But how likely was it that damn would be used then?

Unlike the so-called Anglo-Saxon four-letter swearwords, the gritty, grubby nasty ones which we like to imagine hark back to a harsh medieval life, damn is originally from Latin, and came into English via French. In Latin, damnāre meant ‘to inflict damage upon something’ or ‘to condemn to punishment’.

When damn arrived in English, some time before the fourteenth century, it had a <p> in it, as you can see in these two examples:

‘For hadde God comaundid maydenhede, Than had he dampnyd weddyng with the dede’ (For had God commanded maidenhood, then he had damned marriage with the act (of consummation)). Chaucer, The Wife of Bath (c.1386).

‘He wolde pray god for hym that he myght knowe whether she was dampned or saued’. William Caxton, who introduced the printing press to England (1484).

There are a few theories to explain the appearance of <p> in damn and in words like it (although I should note here that as damn arrived in English from Old French dampner it’s not, strictly speaking, exactly the same).

In Latin, Old French, and Middle English the second syllable of damn when declined was still pronounced (e.g. ‘dam-NED’). The addition of that syllable changes the way the ‘-mn-’ is pronounced. Now, the ‘n’ is silent, but in Middle English it was pronounced.

This consonant cluster falls at a tricky point in the syllable break between making an /m/ with your lips and an /n/ with your tongue on your alveolar ridge (the hard bit behind your upper teeth and before your palate), where you need to coordinate the switch between the two. The mouth’s way of getting around this is to insert a ‘transitional sound’ between them (this is officially called stop epenthesis). In the case of /-mn-/, a /p/ is produced because, like /m/, it has bilabial articulation (both lips). In English this <p> is first seen written down in the thirteenth century, particularly in the West Midlands, and when damn arrived from French it fit in quite nicely with the existing pronunciations.** The <p> was even included in damn when it wasn’t declined. In 1400, ‘I damp þe’ was ‘I damn you’.

You can see this process at work in words like dreamt or empty, where the mouth has to make a /p/ in the process of going from /m/ to /t/. Both dreamt and empty gained a <p> in their spellings in Middle English, but empty is the only word to still have it preserved in its modern spelling. It’s quite a nice fossil.***

Damn started out as a verb, to damn, and over the centuries it has become more versatile, doing all kinds of damn things, like:

becoming an adjective in the fourteenth century (appearing later in, for example, ‘Out damned spot’),

a noun by the seventeenth century (e.g. ‘Frankly my dear, I don’t give a damn‘),

and an interjection (‘Damn!’).

Then, as today, to damn had two main meanings: the first is to imply damnation, to suggest that someone is condemned to Hell. The second is a profane intensifier much like very, as in, YOU DAMN DIRTY APE! (it performs the same function as a slightly swearier very (‘YOU VERY DIRTY APE!’). By the 1500s, the date of the tricky D, this second meaning was definitely in use and it wouldn’t be unexpected to see it in this manuscript.

I just don’t think it was.

Instead, I think this is a mistake, or a false start. You can see in the picture that the ‘d’ is smudged but nothing else is. There are no other smudges on any of the other things written by that person and the letters around it aren’t smudged. I think that this was a half-hearted attempt to rub out the D which may have been an intended damn, or some other word.****

Normally a scribe will correct a mistake by scraping the vellum (animal skin) with the point of a knife. It leaves that spot a bit roughed up, but you can write over it and, if you don’t look too closely, no-one will ever know. Here, for whatever reason, the Sweary Scribbler hasn’t fully erased the mistake. Maybe because there wasn’t a knife-point to hand, or maybe because it’s time-consuming and delicate work and this isn’t formal writing meant to be presented neatly, it’s just a note.

I’m not saying it DEFINITELY wasn’t meant to be a damn(ed) fuckin Abbot, I just think it’s unlikely.

——

* Edward Wilson, ‘A “Damned F–in Abbot” in 1528: The Earliest English Example of a Four-Letter Word’, Notes and Queries (1993), 29-34.

** http://pagines.uab.cat/danielrecasens/sites/pagines.uab.cat.danielrecasens/files/Linguistics.pdf

*** http://www.unioviedo.es/SELIM/revista/resources/Selim-14/06Hebda.pdf

**** My thanks to @mededitor for his input here.

Good article … it was good on Saturday, it’s better now that I can tell you that it is.

I tend to agree with your ‘false start’ notion,

Though the practice of defacing ancient manuscripts intrigues me, would it have been ‘graffiti’ ? Or were the culprits ‘young delinquents’ being naughty, thinking “no-one will see it anyway” ?

Haha, thank you! And thank you for your patience with my inability to cope with buttons on websites.

There are certainly instances of pupils defacing their schoolbooks and of readers doodling in margins. Equally, there are manuscripts – particularly in the later medieval period – where space was left in the margins explicitly for readers to make notes. Even in the most high-status manuscripts (think Lindisfarne Gospels), glossing – the writing of translations between the lines – was commonplace.

I’m by no means an expert on marginalia, but I’d imagine that the accepted use of margins for annotations and glossing opened up the space for any kind of additions, naughty or otherwise.

The ‘fuckin Abbot’ annotator made a series of notes throughout the manuscript, including several manicules (little pointing hands, a bit like drawing an asterisk to mark something important), so they clearly weren’t just graffitiing the pages.

Thanks to @rickglanvill I found you @katemond- just what I needed to brighten the day – following you now

If the d was likely a false start, would you like to hazard a guess what it might’ve meant to be?

Hah! Well that’s a near-impossible question to answer.

As ‘damn’ has already been suggested, I will say that I think it was most likely intended to read ‘O dampnyd abbot’ rather than ‘O dampnyd fuckin abbot’ and the annotator chose ‘fuck’ over ‘damn’, perhaps considering one sin more important than another?

The most interesting read I’ve ever had. I’m going to share this with a friend of mine. She adores the ‘F’ word. She definitely cannot go a day without using it. Hell would be as cold as Antarctica. Hehe :)

Reblogged this on Globe-combing.

That was one of the coolest posts lately.

Reblogged this on BRL MUSIC.

Weird. I’ve always heard that FUCK was originally a contraction – it represented official permission to copulate, due to uncertainty over the cause of the Black Plague. It stood for “Fornication Under Consent (of the) King” – and couples who had such permission were required to display the decree, which of course had the overly enlarged capitol letters running down the left side of the page.

Hi!

Nope, I’m afraid that, and similar acronym stories, are all nonsense. I wrote about it in this post: https://solongasitswords.wordpress.com/2014/02/12/on-the-origin-of-fuck/

The same applies to SHIT being ‘Store High in Transit’.

Great piece!

Reblogged this on theaspiringcaffeinatedlibrarian.

Reblogged this on charlie easterfield and commented:

So glad that I stumbled across this! Not least for the calligraphy, which I love…Would that we could scrape out mistakes off vellum these days!

Nice!

Fantastic post!! :)

Awesome read, very informative and humorous. So, do you think it’s possible they started to write damn, changed their mind and upgraded to ‘fucking’ abbot?

Loved it!

Reblogged this on LUWAGGA ALLAN and commented:

Carnal knowledge.

I shall forever refer to this as the smudge theory now. I like it. It seems to make the most sense.

Fantastic post. I hope the annotator had an inkling that a few hundred years after his apparent ‘graffiti’ in the manuscript, it would be debated, discussed and dabbled around looking for origins that were perhaps simply wrought in his skillful note making , mnemonic writing or simply throwing a word or two around in diabolical liquor excess. :)

That’s a really cool post!!!

Awesome!

Reblogged this on ALEXANDER MOREA.

Pingback: Merry Xmas! An Illustrated History | so long as it's words

Pingback: Falling in Love with Words | The Dictionary of Victorian Insults & Niceties

But what about the explanation of it coming from a older middle or low German word meaning to plant? In which case the use as a metaphor for sex is not all together unlikely. Or are we strictly speaking the written English here?

Pingback: Reading Material, Vol. II | Cheri Lucas Rowlands

He he he we do the repeated one.

Are we going out? Or are we going out out? Meaning are we going to the local or out somewhere where I need to dress up or make more of an effort. Good to know it is an actual thing in language lol.

camsnabera: As far as I was concerned the word FUCK stood for “for unlawful carnal knowledge, which those who practised it were single or married people and were charged in the 18 century for sexual intercourse outside marriiage, single people and adulterers.